【英文原声版06】 Jeffrey Schnapp:The Manifesto of Futurism

一共是100集中文,100集英文,100集翻译节目

每周更新一集中文精制、一集英语原声、一集英文翻译,已经买过就可以永久收听

英文文稿+中文翻译

Zachary Davis: In 18th and19th century Europe, culture was associated with the past. Artistic and literary traditions were steeped in history. Neoclassical movements took inspiration from classical antiquity. Romanticism and Gothic revival drew from the Medieval period. Archaeologists uncovered ancient ruins, artists reproduced sculptures and paintings, and architects constructed buildings with the simplicity and grandeur of ancient Greece and Rome.

十八、十九世纪,欧洲文化与历史息息相关,文学艺术深深扎根于历史传统。新古典主义运动从古典主义作品中汲取灵感,浪漫主义和哥特复兴则归功于中世纪文化。考古学家发掘出了古代遗物,艺术家继承了古典雕塑与画作,建筑师修建起了古朴恢弘的古希腊、古罗马式建筑。

Jeffrey Schnapp:All of those currents that were so central to 19th century culture and that also gave rise to institutions like national libraries, like national museums, likenational archives, institutions devoted not only to conserving the past but worshipping the past.

这些复古风潮一度成为19世纪的文艺主流,推动了国家博物馆、档案馆等文化机构的诞生。这些机构不只是在保存遗物,更是在尊崇过往。

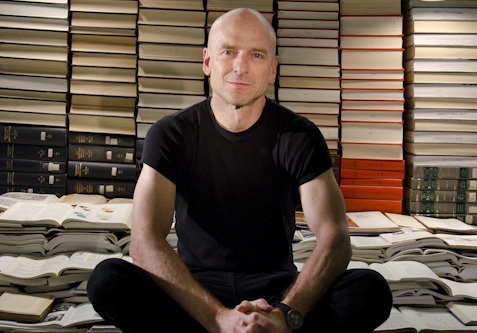

Zachary Davis: That’s Jeffrey Schnapp, a professor of Italian and Comparative Literature at Harvard University. These movements in art, literature, and architecture held up history as the ideal and praised it with almost a religious fervor.

这是哈佛大学意大利文学与比较文学教授杰弗里·施纳普。十八、十九世纪的这些文艺、建筑运动以历史作品为范式,以近乎教徒般的热情对它们尽情讴歌。

Jeffrey Schnapp:It's against all of that futurism launches. It calls for revolution.

未来主义提倡的与这些迥然不同,一场革命性的运动即将展开。

Zachary Davis: Welcome to Writ Large【本课程英文版名称,为喜马拉雅官方自制】, a podcast about how books change the world. I’m Zachary Davis. In each episode, I talk with one of the world’s leading scholars about one book that changed the course of history. In this episode, I talked to Professor Jeffrey Schnapp about The Manifesto of Futurism.

欢迎收听《改变你和世界的一百本书》,在这里我们为大家讲述改变世界的书籍。我是扎卡里·戴维斯。每一集,我都会和一位世界顶尖学者探讨某一本书带给世界的影响。在本集中,我将和哈佛大学教授杰弗里·施纳普讨论《未来主义宣言》。

Zachary Davis: The Manifesto of Futurism was published in 1909, on the front page of Le Figaro, the oldest daily newspaper in France. Its author was Filippo Tomasso Marinetti, a 33-year-old Italian writer who was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1876 and was educated in Egypt and France. With his Manifesto of Futurism, Marinetti launched a new artistic movement that opposed what he called pastism, the worship of the past.

1909年,法国最古老的日报《费加罗报》的头版刊登了《未来主义宣言》。此文的作者是33岁的意大利作家菲利波·托马索·马里内蒂。他于1876年出生在埃及亚历山大港,在埃及和法国读书。马里内蒂的这篇宣言掀起了一场反对过去主义,也就是反对推崇陈旧艺术的运动。

Jeffrey Schnapp:Futurism wants to wipe the slate clean, and to wipe the slate clean, it needed to create a kind of sensational effect, and a sensational effect required a media platform that would have the level of energy associated with it and closeness to the immediate moment of reading of the manifesto.

未来主义意在破旧立新。而要想破旧立新,则需要制造一种轰动效应,这又需要有一个有影响力且贴合大众、迅速吸引人的媒体。

《未来主义宣言》:挥着铁锤的论辩

Manifesto of Futurism: an argument with a hammer

Zachary Davis: The newspaper was the perfect medium. It operated less like the books of the past, and more like the social media networks of today.

当时最理想的媒体便是报纸。它比书籍时效性强,有点类似今天的社交媒体。

Jeffrey Schnapp:It's important to remember that daily newspapers were the closest thing to a live medium in 1909. This is before radio becomes a mass medium, long before television, of course. The front pages of the important dailies really were about as close as you could get to real-time coverage. And therefore, the newspaper is not just an accidental feature of the manifesto. It's the very place, the theater within which the manifesto form is born in its contemporary form.

不过需要注意的是,1909年最类似于直播媒体的之所以是日报,是因为广播在当时尚未成为大众传媒工具,更毋庸说电视。各大日报头版消息的吸睛程度与如今的实况报道别无二致,所以选择报纸发布这则宣言并非偶然。正是在这张诞生了《未来主义宣言》的报纸上,一种现代的文学形式应运而生。

Zachary Davis: Manifestos had historically been associated with religious movements, and especially divisions in main stream religions.

宣言历来与宗教运动有关,尤其是主流宗教的教派纷争。

Jeffrey Schnapp:But typically they were forms of polite argument.

不过这些宣言一般都是温和有礼的辩论。

Zachary Davis: The topic sevolved over time, from mostly religious manifestos to literary manifestos that argued for certain artistic philosophies. But the polite model of argument largely continued.

宣言的主题不断演变,最初基本上都是宗教宣言,后来又衍生出了宣扬某些艺术哲学的文学宣言。不过形式上大多还是彬彬有礼的辩论。

Jeffrey Schnapp: The Futurist Manifesto completely transforms that rhetoric. It is a kind of argument with a hammer, but the hammer is not just the violence of the tone, the violence of the propositions, the emphasis on provocation, but also the use of media as a key vector. The media itself has integrated into the language of provocation.

而《未来主义宣言》如铁榔头般砸烂了这种表面温情。它以激烈的言辞和尖锐的观点挑弄读者的情绪,更让媒体成为其口诛笔伐的媒介,加入到唇枪舌战中。

Zachary Davis: Marinetti harnessed the language of advertisements and machinery and with them built a new form of writing.

马里内蒂精准地拿捏了广告语言和机器的声响,用它们创造出了新的写作形式。

Jeffrey Schnapp: It's a text that really establishes the manifesto as the dominant form that argument will take over the course of the subsequent century. Manifestos from the Futurist Manifesto in 1909 to the present really become the common currency of radical argument for the century as a whole.

这篇宣言标志着在接下来的一百年里,宣言将成为主流的论述形式。从1909年的《未来主义宣言》到如今,过去这近一个世纪里,言辞激烈的论述文章普遍都以宣言的形式发布。

Zachary Davis: The Manifesto of Futurism outlines eleven principles.

《未来主义宣言》概述了十一个原则。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Point one: We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness. Two: courage, audacity and revolt will be the essential elements of our poetry. Three: Up to now, literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, a racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap. Four: we affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched... Much of the thrust of the manifesto is an effort to attack and propose the dismantling of institutions associated with memory, with the past, with the worship of the past.

“一,我们要歌颂追求冒险的热情、劲头十足地横冲直撞的行动。二,英勇、无畏、判逆,将是我们诗歌的本质因素。三,文学从古至今一直赞美停滞不前的思想、痴迷的感情和酣沉的睡梦;我们赞美进取性的运动、焦虑不安的失眠、奔跑的步伐、翻跟头、打耳光和挥拳头。四,我们认为,宏伟的世界获得了一种新的美……”这篇宣言主要意在批判,并建议摧毁一切封存过往、盲目崇拜旧艺术的文化机构。

汽车,比萨莫色雷斯的胜利女神更美

automobile is more beautiful than the Victory at Samoth race

Zachary Davis: What's striking is the Renaissance could be seen as a moment in which the obeisance to the past is ruptured to some degree, but the way you're describing all the subsequent artistic movements, cultural moments that we're aware of, most of them were some kind of revival or renegotiation with a previous form—an acknowledgement that the masters we can imitate and maybe do something new variation. Marinetti seems interested in something radically different, and that seems to be partly why he says, you know, an automobile is more beautiful than the Victory at Samoth race. That there's new creations that have almost the kind of enchanted quality to them that we can celebrate as our own.

令人震惊的是,文艺复兴从某种程度上可以看作对过往的反叛,但您又觉得我们所说的文艺复兴之后的文艺运动,大多是对之前文艺形式的复兴或再度认可,认为我们可以模仿史上名家,并做些许创新。而马里内蒂感兴趣的似乎截然不同,或许也正因此他说汽车比卢浮宫的雕塑《萨莫色雷斯的胜利女神》更为美妙。因为这些崭新的发明完完全全由我们独创,不归别人,自然有种迷人的魔力。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Indeed. He was persuaded, as many people were persuaded at the turn of the 20th century, that this whole world of machinery that was changing the world of work, that was changing the way people moved around the world, that was altering, even beginning to alter aspects of everyday life, which for him is really symbolized, embodied by the automobile, by the rise of these motorized vehicles that are suddenly terrorizing the inhabitants of major cities, that this mechanical civilization represented a complete annihilation, a transformation of all of those currents from the past, and a call, a kind of summons, to create new forms of culture that respond to the opportunities and challenges of the machine age.

20世纪之交时,很多人都坚信机器化正改变着人们的劳动方式、出行方式等方方面面,未来会有翻天覆地的变化。马里内蒂对此也深信不疑。他认为机器化的典型代表就是汽车这类机动车。这些机动车震撼了各大城市的居民,它们所代表的机器文明的兴起意味着一场彻底的湮灭、一场尚古潮流的终结,也呼唤着文艺者们创造一种反映机器时代机遇与挑战的新文化形式。

Zachary Davis: To demonstrate this transformation, Marinetti told a story.

马里内蒂用故事来阐述了自己的观点

Jeffrey Schnapp: The story that the manifesto is framed by is the story of an automobile accident where he and his driver go driving through the streets of Milan and end up in aditch. Their car overturns and it's rising up out of that mud, that kind of industrial mud in the suburbs of Milan, that he becomes a new man, like Paul on the road to Damascus. He becomes the new converted future rises figure. But the Muslim community and it's in that context that he proclaims these principles, which are the founding principles of futurism. Eleven principles that are, in a sense, the kind of rules that are laid out with a hammer to demolish forms of past culture and the worship of the past and to put in their place a whole series of new principles that are focused on the new, the surprising, the extreme, the unexpected, the destructive. But destructive for him always means the creative—that which will give rise to the new.

《未来主义宣言》讲了一起车祸的故事。作者和司机在米兰街上飙车,掉进了一条水沟。车翻了,从水沟里慢慢露出来。作者虽然浑身都是郊区工业污泥,却觉得自己就像保罗在去大马士革的路上蒙召归正那样,整个人都焕然一新。他是新的皈依者,向穆斯林们传播上帝的福音。在这种情况下,他提出了为未来主义奠基这十一条的原则。这些原则一锤粉碎了旧文化形式,破除了人们对它的迷信,取而代之的是一套聚焦于新兴且具备极致张力、出乎意料且极具破坏性文化的原则。作者认为不破不立,毁灭本身也孕育、创造着新生命。

离开斗争就不存在美

There is no more beauty except in struggle

Zachary Davis: The image of creation or newness through destruction—part of this is a generational image, that we have to die for our successors to come forward. And by fetishizing the past, you're suppressing life. And I can't help but think of sort of Nietzschean themes, that life is greater than any abstract principle of, I don't know, love, justice, truth. It's just pure life. And the manifesto itself does praise a kind of aggression and violence even.

破除旧事物、创造新事物似乎是每一代人的惯例,为了子孙后代的发展,我们将不得不撒手离去。迷恋过去就是在压抑生命力。这让我不禁想到尼采哲学中的一大主题——好像是说,生命比爱、正义、真理所有这些抽象原则都要重要,生命不可辜负。《未来主义宣言》甚至还些许赞颂了侵略与暴力。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Indeed. And violence is viewed in the manifesto. And it shapes the language of the manifesto as purgative, as cleansing, as creative, as generative. Just to quote one example from the manifesto, point number 7 is, “There is no more beauty except in struggle.” That kind of sums up right there the basic ethos, which is that struggle is the ultimate expression of vitality. And there is a kind of vitalist model that I think you're alluding to in your question that informs Marinetti’s, I guess I'd call it a kind of metaphysics, that struggle is integral to nature and that art emerges from processes of struggle with the limits of material, with the limits of the body, with the limits of human capacity. But I think what's crucial to that notion is also a new concept of beauty itself, of the aesthetic. You mentioned this famous passage where he proclaims a race car—notice it's a race car, it's not an ordinary automobile—

《未来主义宣言》中确实有暴力元素。作者还一改宣言一贯的语言风格,使之涤荡一切、妙趣横生、影响深远。就拿《未来主义宣言》的第七条来看,“离开斗争就不存在美”。这一定程度上概括了基本要义,那就是斗争是生命力的最终表现形式。有套生命哲学理论影响了马里内蒂某种形而上学的想法,我想你也隐约提到了。这套理论认为矛盾斗争在自然中不可或缺,而艺术诞生于奋力摆脱物质、躯体和人类能力的束缚。不过我觉得还有个因素影响了马里内蒂的想法,那就是一种新的美学概念。你刚刚也提到,作者在宣言里说自己开着一辆赛车,注意他说的是赛车而不是一般的小轿车。

Zachary Davis: You're not talking about a Buick.

对,他说的可不是别克。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Exactly. It's not a Model T, it's a race car, adorned with huge tubes, like soot, like, with the explosive breath of a serpent, you know, he kind of animalizes the figure. He says that automobile, that throbbing, roaring automobile is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace. Well, the Victory of Samothrace was, of course, one of the iconic sculptures from Greek antiquity. It decorated perhaps the most important atrium within the Louvre museum at the time. But what interests him in the race car is not that it's beautiful in a, using the same aesthetic canons as you would use to evaluate the beauty of a sculpture like the Victory of Samothrace. But rather, that beauty is defined not by a series of ideal, abstract, formal, geometrical, universal principles, but rather by intensity. The scale of intensity is the scale of the aesthetic, of a kind of cultural experience, if you like. And in doing so, what he's doing is substituting all of the models of aesthetic appraisal that had shaped the whole prior history of culture, which were all about balance and equilibrium, and asymmetry, and shaping objects to certain kinds of canons of mathematical harmony. For example, think of musical concepts, or think of the architectural concepts that are based on notions like the golden section. Marinetti’s argument is exactly the opposite. Its intensity is the measure of the success of an artwork, for example, or of a political movement for that matter. Impact, intensity, those are the measurements of modern culture, of modern civilization, not the canons of classical harmony or beauty.

嗯,他说的不是那种T型家用车,而是赛车。排气管粗得赛过烟囱,废气直往外喷,发动机像巨蟒般粗喘轰鸣。在他笔下,这车倒更像只猛兽。他说这狂奔嘶吼的跑车美过《萨莫色雷斯的胜利女神》,后者是最负盛名的古希腊雕塑之一,当时藏于卢浮宫最重要的展厅。不过马里内蒂欣赏跑车,并不是因为在传统美学标准下,赛车比这座雕塑更美。他欣赏是因为美不是由一系列理想化、抽象、正式且几何式的原则堆砌决定的,而是由所能激发的情感强度决定的。只要你喜欢,这情感有多强,作品就有多美,带来的文化体验就有多丰富。为此,他摒弃了先前文化史上的所有美学准则,因为它们都在强调协调平衡、非对称、用几何原则构图,比如音乐和建筑设计中“黄金分割”的概念。马里内蒂推崇的恰恰与之相反,他把能否引发情感共鸣视作艺术品或政治运动成功与否的标准。影响力和唤情程度是衡量现代文化乃至现代文明的重要因素,这与古典美学的观点截然不同。

为什么《未来主义宣言》出现在意大利?

Why the Manifesto of Futurism appeared in Italy?

Zachary Davis: I'm sure living in Greece and Italy especially, but Europe in general, in comparison to maybe some of the industrial centers of England and the United States, must have felt staid and slow and sclerotic, maybe politically, maybe culturally.

当时与英美等工业中心相比,整个欧洲大陆,特别是希腊和意大利的政治和文化都僵化停滞、发展缓慢。我相信这些地方的人们当时深有体会。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Italy for him was the country of reference. It was the audience, the ultimate audience of the manifesto right from the start. And the Italian landscape is a landscape where the past is so vividly present, like a kind of palimpsest, because the past encompasses everything from, you know, Greek and Roman and Etruscan remains to many, many other layers of history, all of which coexist with the present. And this urge to destroy, to demolish, to create the tabula rasa could only be so hyperbolic in a context, I think, where there was such an overwhelming sensation of the weight of the past, of the presence of the past, and of it being a burden some presence as well as an animating presence. And so there's no question that the hyperbolic nature of this genre that Marinetti forges, which is the manifesto, really has almost as a prerequisite coming from a landscape like the urban landscape of the great Italian cities. And Venice for him became a symbol of everything that was wrong about the 19th century and more broadly, about the worshipful attitude of the world towards the past.

马里内蒂也觉得意大利就是这样。《未来主义宣言》最初就是在向这个国家发出终极拷问。在意大利的文化图景中,古代文化占据重要一隅,璀璨夺目,包罗了从古代希腊罗马到伊特鲁里亚,再到往后各个时期的文明烙印,恍若旧日重现,与现代文明交相辉映。正因为当时人们一边倒地陶醉在旧文化中,沉醉在这种盲目尊崇中,以至于这种勃勃生机反倒成了某种负累,《未来主义宣言》中那股想要摧枯拉朽、改弦更张的欲望才会如此夸张。也难怪马里内蒂的这篇文章和这种风格如此夸张的题材会诞生于意大利大城市的文化土壤中,估计这也是它诞生的前提。在他看来,威尼斯当时弥漫着崇尚十九世纪乃至一切旧时文化的错误思想。

Zachary Davis: As Marinetti presented it, he and his fellow Futurists were crushing the past to pave the way for the future. But the irony is that Marinetti came from the very culture that he was critiquing.

正如马里内蒂所说,他和其他未来主义者是在砸碎过往的镣铐,为未来发展奠基。不过颇具讽刺意味的是,他自己倒是成长于他所批判的文化环境。

Jeffrey Schnapp: His career was launched largely as a kind of ecadentist poet. He had very close connections to the circle of symbolist, late symbolist poets that he denounces actually in several subsequent futurist literary manifestos. And out of that experience, futurism really was born as a kind of revolt from within, you might say.

马里内蒂最初是一位象征主义诗人。他和象征主义诗人的圈子交往密切,但在之后的几篇未来主义宣言中他对这几位后期象征主义诗人都进行了批判。据此我们可以说,未来主义不失为对自身的反叛。

Jeffrey Schnapp: I think what's at the core of his poetic career is this transition from latesymbolism—which is a kind of expression of a sort of late romanticism, youmight say—to a poetry that aspires to become the poetry of the age of industry, a poetry of the age of the machine age, and to find ways not only to bring poetry into the streets, so to speak, but also to change the nature of language, the range of expressivity that is available to poetry and to all artforms, by literally contaminating them with other forms. The sounds of motors, to bring noise into poetry, to use typography to disrupt the harmony of the page, that harmony that took centuries of work from Gutenberg to the industrialization of printing in the 19th century—to blow all of that up in the name of creating new forms of expression that would be adequate to the nature of the machine age, which is an age where not only are humanbeings constantly engaged in interacting with machines, where the life of machines is part of the life of society, but also where machines have agency, machines are actors, and machine language becomes part of the language of poetry itself as a way of expanding its contours. So it's that contamination of realms in the name of breaking with old molds and bringing all forms of human expression into the present and thereby into the future, that represents the core ambition and a real break with where he came from as a poet.

我认为他诗歌生涯的重要转折是从后期象征主义,或者说晚期浪漫主义,转向一种全新的诗歌类型。他想要用这种新类型缔造属于工业和大机器时代的诗歌,不只要让它们在街头被传诵,更要彻底改变诗歌语言,在诗歌中糅入其他形式,从而突破诗歌和其他艺术形式的表现界限。他把马达轰鸣等噪音带入诗歌;他用排版打破页面的整齐划一,打破了从古登堡时代到十九世纪工业印刷间,这数百年里人们孜孜以求的页面样式,理由是要创造新的符合机器时代本质的表现形式。他认为机器时代的本质不仅在于人类与机器共舞、机器参与社会生活,更在于机器可以是主体,可以在文学艺术中享有一席之地,机器的声响可以融入诗歌语言,参与诗歌实验。马里内蒂以破除陈腐形式、为当下乃至未来读者展现人类所有表现形式为名,尝试糅合了多种艺术表现形式。这些尝试展现了他的宏图大志以及身为诗人所取得的重大突破。

报纸,新文化的试验场

Newspaper, a laboratory of new culture

Zachary Davis: The manifesto embraced a different, not traditionally poetic form of publishing: the newspaper.

《未来主义宣言》在报纸上发布,这与传统上诗情画意的出版方式大不相同。

Jeffrey Schnapp: What he saw in the mediasphere of 1909 was that a new kind of set of forces were being placed together. One, newspapers communicate around along multiple channels. Like the newspaper is already a multi-channel kind of platform. You have multiple stories, multiple typefaces. You have the beginnings of visual and verbal inter mixing. You have the beginnings of photography being, inter secting narrative storytelling, journalistic accounts. And also, especially important, the use of telegraphy to relay stories across the world in real time. And therefore networks that are enabling the newspaper front page to be increasingly a place where stuff that is happening now or that was just emerging or just happening is all co-present at the same time. That's the laboratory that futurism is trying to create a new culture within. And it's the laboratory within which 20th century and 21st century culture continues tobe created. But to get there, culture, as well as forms of persuasion, had tochange their style. And the Founding Manifesto of Futurism, it enacts thatshift in style. There's lots of parts of it that belong to the past, but at the core of it, what's kept it alive, what's made it one of those really important seminal documents is the way it codified a new style of communication and of argument.

马里内蒂发现在1909年的媒体界,几股趋势同时涌现。报纸上信息的呈现方式变得多样,刊登着以各种字体印刷的各种消息,仿佛报纸本身就是种多元平台。报业开始开始糅合多种视觉文字形式,在新闻报道中加入照片报业还开始运用电报技术实时采集传播讯息。这些趋势的出现,让报纸头版可以实时刊登各类新闻和突发事件。也正因此,报纸得以成为未来主义者们垦荒的试验田,成为20、21世纪文化创新发展的阵地。不过若想要在报纸上刊登连载,传统的文化风格以及论述文本的风格都要略作修改。《未来主义宣言》便实现了这种风格的转变。它虽然还带着旧文化的烙印,但从根本上讲,它之所以影响深远,在今天依然展现着重要价值,是因为它确立了一种新的论述交流形式。

Zachary Davis: How did this text change media practices in ways that are still with us? What are the patterns that are recognizable?

《未来主义宣言》对媒体有什么持续至今的影响呢?有哪些易于察觉的典型影响?

Jeffrey Schnapp: A couple of things come to mind right away. This is a text woven out of slogans. It is designed not to be read the way you would read a conventional scientific or scholarly article or a long form of argumentation, but rather to be read as a construction made out of snippets. Therefore, it doesn't make arguments the way that a conventional scientific or scholarly argument would be made with logical steps leading in a kind of smooth progression to some kind of culbert culminating hypothesis. On the contrary, it proclaims. It violates the rules of evidence. It makes counter factual assertions. It deliberately engages in polemic for polemic sake. I would cite as an example of that one of its most famous passages, one of the passages that really stirred up readers both in France and throughout the world, because the manifesto was immediately translated into about 25 languages within two years of its initial publication, which was proposal number 10, which reads as follows: “We demand the destruction of museums, libraries, academies of all kinds, and will combat moralism, feminism and each cowardly form of opportunism and utilitarianism.” That's a mouthful of a list. You notice not only are we going to destroy three of the great defining institutions of the 19th century, the senational institutions that gathered books, artworks, and historical records. But also we're going to combat what he calls moralism, what he calls feminism, and all forms of cowardly opportunism and utilitarianism. That’s not a cohesive proposal. And most of the proposals are similarly interestingly cobbled together to get the maximum reaction on the part of the audience, but not to make an argument in the, a kind of logical sense. They deliberately create a different logic, which is more that of advertising. I would say. Very concise, compact forms of communication. The logo.

你一说,我就马上想到了几点。这篇宣言充斥着口号,作者无意让读者像阅读常规学术文章或长篇论述文那样去读它,而是让他们碎片化阅读。所以它也不像那些学术文章一样逻辑缜密、环环相扣,直至推向高潮,佐证某种假设。它并没有在规规矩矩地论证,而只是单纯在呼吁,提出反事实的主张。它特意面红耳赤地争论辩护,以求越辩越明。《未来主义宣言》在初次刊登的两年内就被译成了约25种文字,反响热烈。就拿宣言的第十条来说吧,这条宣言在法国乃至全世界都引起轩然大波,内容是:“我们要摧毁一切博物馆、图书馆和科学院,向道德主义、女权主义以及一切卑鄙的机会主义和实用主义的思想开战。”这只是众多提议之一。值得注意的是,作者不仅呼吁要摧毁这些收藏图书、艺术作品和史料的上世纪重要文化机构,还要反对他所谓的道德主义、女权主义以及一切卑鄙的机会主义和实用主义。这两者其实并无太大关联。宣言中的多数提议都以类似方式有趣地拼凑在一起,以求能最大程度地吸引读者,而不是要在逻辑上严丝密合。这些提议就这么摞在一起,构成的语篇逻辑倒更像是广告,像那些简洁紧凑的广告语。

Zachary Davis: Just do it.

就像耐克的广告语“Just do it”。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Just do it. Exactly. What does that mean? It means everything and nothing. The swoosh: same. It's that compression of communication and the transportability of the, the short forms across platforms, across conversations, across domains, that makes this a very, very powerful communication strategy.

没错。这句话什么意思呢?似乎意犹未尽,又似乎什么都没说。耐克的logo也是一样的道理。但正是信息的紧凑排布和短篇幅易于跨平台、跨领域传播的特性,让这种沟通方式有力且有效。

Zachary Davis: Is Marinetti, do you think, either accommodating himself to the belief that we're driven more by the passions and by the heart than by the brain. Or does he want to live in a world in which we do. And so he tailors his rhetoric to match that kind of media or rhetorical culture?

马里内蒂转变自己的文风,让它更贴合这种紧凑短平的媒体风格。您觉得他这样做,是因为相信人们大多追随内心激情胜过理性,还是因为他想要与时俱进呢?

Jeffrey Schnapp: He, like many critics of the society of this period, had a deep aversion to what was referred to then as positivism, to the models of science, kind of responsible social beliefs, and the revolution futurism is launching and that theism stands for is really a revolt against those forms. So, intensifying embodiment. Getting close to the gut, away from the brain, away from contemplative models into active, hyperactive even, models of being, for him is really essential to the transformation of society and culture that he is trying to enact in the arts. Initially, it's, the focus of futurism is sharply on the arts. Gradually it expands out to all domains of contemporary life. And sensationalism, which is a word that we continue to associate with the press, you know, the tabloid press in particular, really comes from this period. The emergence of a media sphere that's all about that kind of quick sort of like headline that grabs you, whose ultimate and true audience is the distracted reader, not the dedicated reader, not the contemplative quiet reader who's sitting in a library or in a gentlemen's study, but rather somebody on the bus, walking down a street, seeing a broadside on a wall, a kind of reading situation like that. That's the world that these new forms that futurism wants to incubate and promote in the world of poetry and the world of the arts and the world of performance in the world of architecture and eventually in all kinds of other domains of everyday life. And they are closely associated with getting away from a kind of cerebralist culture, which was felt to be somehow deeply implicated in the decline of culture and civilization in the second half of the 19th century.

马里内蒂与同时代的许多批评家一样,旗帜鲜明地反对实证主义与科学模型。当时掀起的未来主义运动以及未来主义理念正是对这些的反叛。未来主义者带着满腔热血投身创新,不去关注什么合乎逻辑,也摒弃了严谨温和的艺术形式,转而推崇积极火热甚至稍显激进的形式。可以说马里内蒂对这种社会文化的剧变功不可没。未来主义的关注点最初仅限于艺术,后来慢慢拓展到了现代生活的方方面面。媒体,尤其是通俗小报那种延续至今的博眼球风格其实也是从那时兴起的。媒体界当时充斥着吸睛的短标题。这些媒体内容的目标读者并非那些专心致志地坐在图书馆或书房里静默沉思的人,而是注意力被形形色色事情分散的人——他们在公交车上或马路边四处张望,时不时瞅一眼墙上的告示。未来主义者希望把这种新形式推广到诗歌、艺术、建筑乃至社会生活的方方面面。他们还力求破除理性至上主义,认为19世纪后半叶文化衰落与它有关。

Zachary Davis: Even as Marinetti called for a new, future-focused movement, he acknowledged that his own works would one day represent the past. In order for his movement to succeed, the writers and artists who came later would have to displace him.

尽管马里内蒂呼吁一场全新的、面向未来的运动,但他毫不避讳地说这场运动总有一天也会被贴上旧标签。为了践行未来主义运动的宗旨,他任由甚至鼓励后世的文学家、艺术家取代自己的位置。

Jeffrey Schnapp: The manifesto closes with an invitation, literally an invitation for a next generation to come and bury the very revolution that the manifesto is proclaiming on the front page of the newspaper. Even as that revolution is barely starting, already the moment where it will be overcome by a subsequent revolution is anticipated. And I think that is a profound expression of what strikes me as really radical, but also makes this a kind of monumental gesture with respect to forms of cultural polemic and conversation in the whole subsequent history of culture and politics.

在结尾处,《未来主义宣言》的作者发起了一场号召。他号召下一代人将这起由报纸头版文章掀起的未来主义运动抛在脑后。尽管宣言发表时未来主义运动只是初见端倪,但不难想象它也会被后世的文艺运动扫出历史舞台。结尾的号召让我切切实实感受到这篇宣言有多激进,也让它成为了后世文化与政治中有关文化对话辩论的一座丰碑。

新的人文议题,新的公民

a new human subject, a new citizen

Zachary Davis: Yeah, I think what's striking to me was he wasn't saying we have developed the final, the final artform, and this is the best and will stand the test of time. It was, we've got 10 years of creativity and then when we're 40, we're done. You know, he says, let’s see, “The oldest of us is 30, so we have at least a decade for finishing ourwork. When we are 40, other younger and stronger men will probably throw us inthe waste basket like useless manuscripts. We want it to happen!” That's amazing. And it's, I think because of that, consistent with a kind of generative cycle of destruction and, and rebirth, which is kind of extraordinary. And I couldn't help but feel in this a really, I think probably a unique orientation away from respect and veneration for elders and their wisdom towards youth and their creativity. I mean, this is, to me, this document fits in San Francisco rather well. And I wonder, you know, could you contextualize this or place this in conversation with like, when did youth culture start to acquire some of these qualities that are still with us today? I mean, ageism is really devastating for many people in the country. And he's saying, well, that's how it should be. We should be thrown away in the garbage.

没错,最震撼我的是,马里内蒂没有说自己提出了文学艺术的终极形式,没有说自己提出的形式能禁得起时间的永久考验。打比方说,我们四十岁就被取代,还剩十年的创作时间。他对这个的看法是:“我们当中最老的已经三十了,还有至少十年能给我们的作品收尾。四十岁一到,优秀的后辈或许会对我们的作品嗤之以鼻,把它们看作破东烂西。这反而是我想要的。”这太了不起了。也正因此,每一代人都可以不断破旧立新,带来非比寻常的进步。我觉得这篇宣言的气质很像旧金山,它对尊敬前辈不怎么感冒,反而展现了老一辈对年轻人包容和对他们创造力的欣赏。从年龄歧视的角度,您如何看待这篇宣言呢?从什么时候起,青年文化中出现了如今这种不太尊老的特点呢?年龄歧视在美国有些地方还挺严重的。但马里内蒂觉得这样理所当然,我们就应该对旧的东西嗤之以鼻。

Jeffrey Schnapp: Indeed. Yeah. I think it's really in the context of these kinds of revolts, of which futurism is just one, but, but it's a significant one. Also in the context of other radical political movements of the same era, the anarchist movement, parts of the socialist movement as well, were very focused on creating a new kind of type of humanity. The idea of a new human subject, a new citizen, a new political subject, is integral to many of the revolutionary doctrines that define the history of the 20th century. And futurism is aligned with those trends, and precisely the rhetoric you were alluding to, this rhetoric of change for change's sake, of constant transformation, of one way of displacing the next places, the focus of the action of history, on the stage of history, on youth.

嗯,我觉得需要将它放在大背景下看,当时盛行着各种反叛旧文化的风潮,未来主义不是唯一一个,却是影响最大的一个。而且在当时,无政府主义等激进的政治运动也注重塑造新人类。整个20世纪思想史上大多都是这种革命性的新理念,它们往往关注新的人文议题、新公民和新的政治议题。未来主义符合这一潮流,也就是你之前想说的不停地为变革而变革、反复取代、关注时代动向和年轻一代。

Zachary Davis: Marinetti’s legacy lives on, both through the Futurist movement and the manifesto form.

得益于未来主义运动和新的宣言形式,马里内蒂的影响一直持续到今天。

Jeffrey Schnapp: The movement continued until 1944, really until his death, and has continued to have a huge impact on the different cultural, political, avant garde movements of the post-World War Two period to the, to the present. There are manifestos written pretty much for every single cultural and political movement you can think of from this time to the present, including cybernetic manifestos. I myself have written several manifesto in different—

未来主义运动持续到了1944年马里内蒂去世,在此之后还继续影响着多种文化、政治以及二战后的前卫运动,并持续至今。时至今日,几乎所有的政治文化运动都会催生出大量宣言,甚至还有关于控制论的宣言。我自己也写了几份宣言。

Zachary Davis: I have read your manifestos.

我拜读过您的宣言。

Jeffrey Schnapp: —activities I've been involved in. It just became a genre that is across between the oretical and philosophical and critical argument and advertising and pamphleting. It's a tool that's just part of the core tool kit of modern culture.

这几份宣言是我参加活动时写的。宣言现在成了一种独特的体裁,介于理论与哲学著作、批判性论述文、广告和宣传册之间。它显然成了现代文化中不可或缺的创作方式。

Zachary Davis: The Manifesto of Futurist channeled the power and imagery of machinery, destruction, and progress to shift the creative focus from classical antiquity to the innovations of the day. But the text also help create a broader change in how we think, write, and speak today. In some ways, we’re all futurists now.

《未来主义宣言》描绘了机器与破坏这些意象,展现了它们的力量,也让文艺创作的重心从赞美古代遗物转向讴歌现代生活。宣言还改变了我们思考、写作和说话的方式。从这方面看,我们其实都是未来主义者。

Zachary Davis: Writ Large is an exclusive production of Ximalaya. Writ Large is produced by Galen Beebe and me, Zachary Davis, with help from Feiran Du, Ariel Liu, Wendy Wu, and Monica Zhang. Music is by Blue Dot Sessions. Don’t miss an episode. Subscribe today in the Ximalaya app. Thanks for listening.

WritLarge是喜马拉雅旗下的独家播客节目。Writ Large由本人Zachary Davis和Galen Beebe制作,Feiran Du、Ariel Liu、Wendy Wu和Monica Zhang为本节目提供了大力支持,背景音乐由Blue Dot Sessions提供。节目集集精彩,不容错过,快来喜马拉雅app订阅吧。感谢您的收听,我们下期再见!

- 【中文精制版06】杰弗瑞·施耐普《未来主义宣言》| 向一切旧传统宣战2.86万19:38

- 【英文原声版06】 Jeffrey Schnapp:The Manifesto of Futurism2.18万26:58

- 【英文翻译版06】杰弗瑞·施纳普:《未来主义宣言》1.99万22:15

- 【中文精制版07】劳伦斯·萨默斯:《就业、利息和货币通论》| 经济危机时代的救市宝典6.83万32:14

- 【英文原声版07】Larry Summers: The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money2.27万25:23

- 【英文翻译版07】劳伦斯·萨默斯:《就业、利息和货币通论》1.88万18:18

- 【中文精制版08】朵丽丝-索默:《审美教育书简》| 审美:反拨理性,救赎理性4.30万28:47

- 【英文原声版08】Doris Sommer: Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man1.91万27:00

- 【英文翻译版08】朵丽丝-索默:《审美教育书简》1.76万26:39

- 【中文精制版09】菲利普-德洛里亚:《黑麋鹿如是说》| 印第安人的圣经5.54万33:46

- 艺术人生_gz

既然有了中文版,为啥还要有英文版加中文翻译? 真是画蛇添足,不喜欢

维琪没有强迫症 回复 @艺术人生_gz: 因为很多用户提出了需求,我们总是以尽量满足用户需求为己任呢~

- 18613733kaa

中英对照自然有人需要,很好的学习机会

程橙橙C 回复 @艺术人生_gz: 为啥不是?这个方法练习学术英语很好,我们学人文社科的非常需要,尤其是参加各种国际学术会议前听一听,有不熟悉的地方也可以对照看一看,顺一顺语感和表达方式,对我们会议发言很有帮助。

- 采采芣苢898

教授的思路好清晰,虽然原声版很详细,但是感觉信息比较零碎,听完后要再听下精华版,帮我更好的梳理了课程的内容

- 读书永不眠

惊喜发现有英文加中文版了。在同一文件中进行双语流畅阅读,方便一段一段中英文对照学习!!👏👏🤓🤓

维琪没有强迫症 回复 @读书永不眠: 喜欢就好,嘿嘿~

- JJ2013

喜欢中英对照的文稿!谢谢!

- molly茂林

这张的中英文对照非常棒。谢谢!这样就足够,不用再专门做个英文翻译版,节省精力把内容打磨得更好

- 1398975yivc

那大字报的祖宗是不是这篇文章呢?

- 大大方读

讲到媒体影响,的确碎片化阅读已是常态,而视频媒介大有后来居上的态势,现代人除了提升这些现代性阅读的能力,也要能回归纸质阅读,就好比说在收听这个节目后,买了其中的一本(多本是真爱)去慢慢读。

- 次方思想家

感觉像是一群社会小青年

一共100集,每周更新一集,这就需要100个星期,两年,也太慢了吧

维琪没有强迫症 回复 @听友184344754: 是为了让大家两年都有新节目可以听哦,每周一期(3集)实在是因为为了保证质量