冠军小丹尼 英文名著|第20章

The big shiny silver Rolls-Royce had braked suddenly and come to a stop right alongside the filling-station. Behind the wheel I could see the enormous pink beery face of Mr Victor Hazell staring at the pheasants. I could see the mouth hanging open, the eyes bulging out of his head like toadstools and the skin of his face turning from pink to bright scarlet. The car door opened and out he came, resplendent in fawn-coloured riding-breeches and high polished boots. There was a yellow silk scarf with red dots on it round his neck, and he had a sort of bowler hat on his head. The great shooting party was about to begin and he was on his way to greet the guests.

He left the door of the Rolls open and came at us like a charging bull. My father, Doc Spencer and I stood close together in a little group, waiting for him. He started shouting at us the moment he got out of the car, and he went on shouting for a long time after that. I am sure you would like to know what he said, but I cannot possibly repeat it here. The language he used was so foul and filthy it scorched my earholes. Words came out of his mouth that I had never heard before and hope never to hear again. Little flecks of white foam began forming around his lips and running down his chin on to the yellow silk scarf.

I glanced at my father. He was standing very still and very calm, waiting for the shouting to finish. The colour was back in his cheeks now and I could see the tiny twinkling wrinkles of a smile around the corners of his eyes.

Doc Spencer stood beside him and he also was very calm. He was looking at Mr Hazell rather as one would look at a slug on a leaf of lettuce in the salad.

I myself did not feel quite so calm.

‘But they are not your pheasants,’ my father said at last. ‘They’re mine.’

‘Don’t lie to me, man!’ yelled Mr Hazell. ‘I’m the only person round here who has pheasants!’

‘They are on my land,’ my father said quietly. ‘They flew on to my land, and so long as they stay on my land they belong to me. Don’t you know the rules, you bloated old blue-faced baboon?’

Doc Spencer started to giggle. Mr Hazell’s skin turned from scarlet to purple. His eyes and his cheeks were bulging so much with rage it looked as though someone was blowing up his face with a pump. He glared at my father. Then he glared at the dopey pheasants swarming all over the filling-station. ‘What’s the matter with ’em?’ he shouted. ‘What’ve you done to ’em?’

At this point, pedalling grandly towards us on his black bicycle, came the arm of the law in the shape of Sergeant Enoch Samways, resplendent in his blue uniform and shiny silver buttons. It was always a mystery to me how Sergeant Samways could sniff out trouble wherever it was. Let there be a few boys fighting on the pavement or two motorists arguing over a dented bumper and you could bet your life the village policeman would be there within minutes.

We all saw him coming now, and a little hush fell upon the entire company. I imagine the same sort of thing happens when a king or a president enters a roomful of chattering people. They all stop talking and stand very still as a mark of respect for a powerful and important person.

Sergeant Samways dismounted from his bicycle and threaded his way carefully through the mass of pheasants squatting on the ground. The face behind the big black moustache showed no surprise, no anger, no emotion of any kind. It was calm and neutral, as the face of the law should always be.

For a full half-minute he allowed his eyes to travel slowly round the filling-station, gazing at the mass of pheasants squatting all over the place. The rest of us, including even Mr Hazell, waited in silence for judgement to be pronounced.

‘Well, well, well,’ said Sergeant Samways at last, puffing out his chest and addressing nobody in particular. ‘What, may I hask, is ’appenin’ around ’ere?’ Sergeant Samways had a funny habit of sometimes putting the letter h in front of words that shouldn’t have an h there at all. And as though to balance things out, he would take away the h from all the words that should have begun with that letter.

‘I’ll tell you what’s happening round here!’ shouted Mr Hazell, advancing upon the policeman. ‘These are my pheasants, and this rogue,’ pointing at my father, ‘has enticed them out of my woods on to his filthy little filling-station!’

‘Hen-ticed?’ said Sergeant Samways, looking first at Mr Hazell, then at us. ‘Hen-ticed them, did you say?’

‘Of course he enticed them!’

‘Well now,’ said the sergeant, propping his bicycle carefully against one of our pumps. ‘This is a very hinterestin’ haccusation, very hinterestin’ indeed, because I ain’t never ’eard of nobody hen-ticin’ a pheasant across six miles of fields and open countryside. ’Ow do you think this hen-ticin’ was performed, Mr ’Azell, if I may hask?’

‘Don’t ask me how he did it because I don’t know!’ shouted Mr Hazell. ‘But he’s done it all right! The proof is all around you! All my finest birds are sitting here in this dirty little filling-station when they ought to be up in my own wood getting ready for the shoot!’ The words poured out of Mr Hazell’s mouth like hot lava from an erupting volcano.

‘Am I correct,’ said Sergeant Samways, ‘am I habsolutely haccurate in thinkin’ that today is the day of your great shootin’ party, Mr ’Azell?’

‘That’s the whole point!’ cried Mr Hazell, stabbing his forefinger into the sergeant’s chest as though he were punching a typewriter or an adding machine. ‘And if I don’t get these birds back on my land quick sharp, some very important people are going to be extremely angry this morning. And one of my guests, I’ll have you know, Sergeant, is none other than your own boss, the Chief Constable of the County! So you had better do something about it fast, hadn’t you, unless you want to lose those sergeant’s stripes of yours?’

Sergeant Samways did not like people poking their fingers in his chest, least of all Mr Hazell, and he showed it by twitching his upper lip so violently that his moustache came alive and jumped about like some small bristly animal.

‘Now just one minute,’ he said to Mr Hazell. ‘Just one minute, please. Am I to understand that you are haccusin’ this gentleman ’ere of committin’ this hact?’

‘Of course I am!’ cried Mr Hazell. ‘I know he did it!’

‘And do you ’ave any hevidence to support this haccusation?’

‘The evidence is all around you!’ shouted Mr Hazell. ‘Are you blind or something?’

Now my father stepped forward. He took one small pace to the front and fixed Mr Hazell with his marvellous bright twinkly eyes. ‘Surely you know how these pheasants came here?’ he said softly.

‘Surely I do not know how they came here!’ snapped Mr Hazell.

‘Then I shall tell you,’ my father said, ‘because it is quite simple, really. They all knew they were going to be shot today if they stayed in your wood, so they flew in here to wait until the shooting was over.’

‘Rubbish!’ yelled Mr Hazell.

‘It’s not rubbish at all,’ my father said. ‘They are extremely intelligent birds, pheasants. Isn’t that so, Doctor?’

‘They have tremendous brain-power,’ Doc Spencer said. ‘They know exactly what’s going on.’

‘It would undoubtedly be a great honour,’ my father said, ‘to be shot by the Chief Constable of the County, and an even greater one to be eaten afterwards by Lord Thistlethwaite, but I do not think a pheasant would see it that way.’

‘You are scoundrels, both of you!’ shouted Mr Hazell. ‘You are rapscallions of the worst kind!’

‘Now then, now then,’ said Sergeant Samways. ‘Hinsults ain’t goin’ to get us nowhere. They only haggravate things. Therefore, gentlemen, I ’ave a suggestion to put before you. I suggest that we all of us make a big heffort to drive these birds back over the road on to Mr ’Azell’s land. ’Ow does that strike you, Mr ’Azell?’

‘It’ll be a step in the right direction,’ Mr Hazell said. ‘Get on with it, then.’

‘’Ow about you, Willum?’ the sergeant said to my father. ‘Are you agreeable to this haction?’

‘I think it’s a splendid idea,’ my father said, giving Sergeant Samways one of his funny looks. ‘I’ll be very glad to help. So will Danny.’

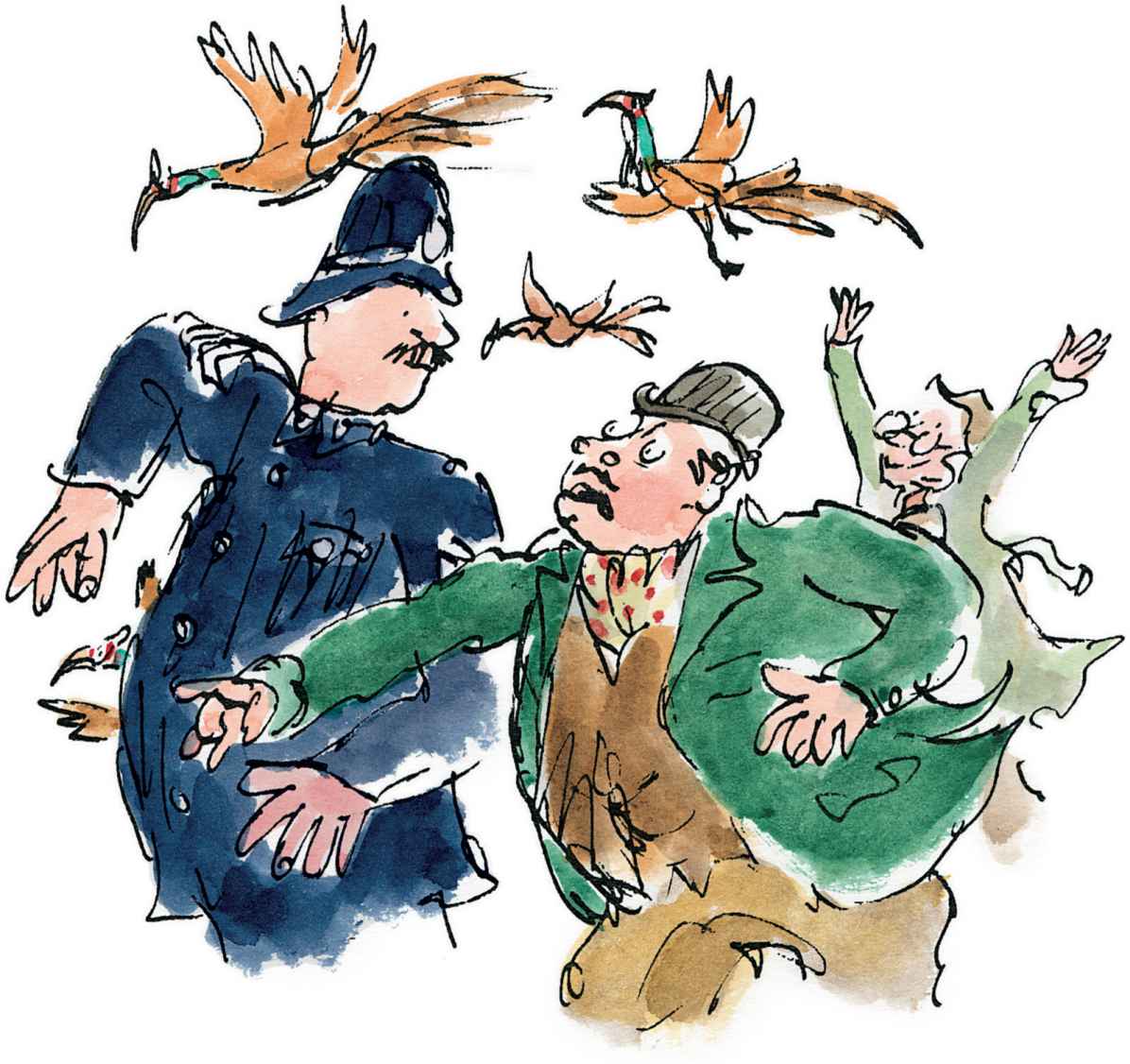

What’s he up to now, I wondered, because whenever my father gave somebody one of his funny looks, it meant something funny was going to happen. And Sergeant Samways, I noticed, also had quite a sparkle in his usually stern eye. ‘Come on, my lads!’ he cried. ‘Let’s push these lazy birds over the road!’ And with that he began striding around the filling-station, waving his arms at the pheasants and shouting ‘Shoo! Shoo! Off you go! Beat it! Get out of ’ere!’

My father and I joined him in this rather absurd exercise, and for the second time that morning clouds of pheasants rose up into the air, clapping their enormous wings. It was then I realized that in order to fly across the road, the birds would first have to fly over Mr Hazell’s mighty Rolls-Royce which lay right in their path with its door still open. Most of the pheasants were too dopey to manage this, so down they came again smack on top of the great silver car. They were all over the roof and the bonnet, sliding and slithering and trying to keep a grip on that beautifully polished surface. I could hear their sharp claws scraping into the paintwork as they struggled to hang on, and already they were depositing their dirty droppings all over the roof.

‘Get them off!’ screamed Mr Hazell. ‘Get them away!’

‘Don’t you worry, Mr ’Azell, sir,’ Sergeant Samways cried out. ‘We’ll fix ’em for you. Come on, boys! Heasy does it! Shoo ’em right over the road!’

‘Not on my car, you idiot!’ Mr Hazell bellowed, jumping up and down. ‘Send them the other way!’

‘We will, sir, we will!’ answered Sergeant Samways.

In less than a minute, the Rolls was literally festooned with pheasants, all scratching and scrabbling and making their disgusting runny messes over the shiny silver paint. What is more, I saw at least a dozen of them fly right inside the car through the open door by the driver’s seat. Whether or not Sergeant Samways had cunningly steered them in there himself, I didn’t know, but it happened so quickly that Mr Hazell never even noticed.

‘Get those birds off my car!’ Mr Hazell bellowed. ‘Can’t you see they’re ruining the paintwork, you madman!’

‘Paintwork?’ Sergeant Samways said. ‘What paintwork?’ He had stopped chasing the pheasants now and he stood there looking at Mr Hazell and shaking his head sadly from side to side. ‘We’ve done our very best to hencourage these birds over the road,’ he said, ‘but they’re too hignorant to hunderstand.’

‘My car, man!’ shouted Mr Hazell. ‘Get them away from my car!’

‘Ah,’ the sergeant said. ‘Your car. Yes, I see what you mean, sir. Beastly dirty birds, pheasants are. But why don’t you just ’op in quick and drive ’er away fast? They’ll ’ave to get off then, won’t they?’

Mr Hazell, who seemed only too glad of an excuse to escape from this madhouse, made a dash for the open door of the Rolls and leaped into the driver’s seat. The moment he was in, Sergeant Samways slammed the door, and suddenly there was the most infernal uproar inside the car as a dozen or more enormous pheasants started squawking and flapping all over the seats and round Mr Hazell’s head. ‘Drive on, Mr ’Azell, sir!’ shouted Sergeant Samways through the window in his most commanding policeman’s voice. ‘’Urry up, ’urry up, ’urry up! Get goin’ quick! There’s no time to lose! Hignore them pheasants, Mr ’Azell, and haccelerate that hengine!’

Mr Hazell didn’t have much choice. He had to make a run for it now. He started the engine and the great Rolls shot off down the road with clouds of pheasants rising up from it in all directions.

Then an extraordinary thing happened. The pheasants that had flown up off the car stayed up in the air. They didn’t come flapping drunkenly down as we had expected them to. They stayed up and they kept on flying. Over the top of the filling-station they flew, and over the caravan, and over the field at the back where our little outdoor lavatory stood, and over the next field, and over the crest of the hill until they disappeared from sight.

‘Great Scott!’ Doc Spencer cried. ‘Just look at that! They’ve recovered! The sleeping pills have worn off at last!’

Now all the other pheasants around the place were beginning to come awake. They were standing up tall on their legs and ruffling their feathers and turning their heads quickly from side to side. One or two of them started running about, then all the others started running; and when Sergeant Samways flapped his arms at them, the whole lot took off into the air and flew over the filling-station and were gone.

Suddenly, there was not a pheasant left. And it was very interesting to see that none of them had flown across the road, or even down the road in the direction of Hazell’s Wood and the great shooting party. Every one of them had flown in exactly the opposite direction!

还没有评论,快来发表第一个评论!